Conway's Game of Life

The so-called 'Game of Life' (or simply 'Life' as it is known by aficionados) is not the popular board game from the 1980's, but rather a simple set of rules that gives rise to a lot of curious and fascinating behaviour.

↑ Not this one, this one! ↓

The Game of Life is 'played' on an infinite plane of squares (a 'board'), where each square is called a cell, and cells can be either alive or dead.

The rules are as follows:

- Living cells die of loneliness if they don't have enough neighbours. (< 2)

- Living cells die of starvation if they have too many neighbours. (> 3)

- Dead cells spring to life if they have the right number of live neighbours. (3)

If the board starts off empty, with no living cells, then nothing ever happens. Boring! But if the board starts off with any few random cells alive, then all sorts of things might occur. Patterns appear and disappear, new shapes emerge and evolve, in an ever shifting feast of marvellous wonder.

The 'game' (it's referred to as a game for zero players) was discovered by John Conway in 1969, when he was supposed to be working on other things. He and his colleagues spent "about 18 months of coffee time" before they arrived at a set of rules that give a maximally interesting result.

Patterns that can be created have been extensively studied, and are categorised in a number of ways. There is a rich glossary of terms that have arisen around the game.

This type of game is called a Cellular Automata. There are many other examples of cellular automata, and they are used for many purposes.

Cells in the hood

The 'neighborhood' used in Game of Life (abbreviated as 'GOL', or, sometimes, 'Life') is the 8 cells which are diagonally, horizontally or vertically adjacent to the current cell. Different CA use different definitions of neighborhood.

RLE (Run Length Encoding) is a common way to share interesting set ups for Life.

Short Note on History

Discovered by John Conway, perfected over "many coffeebreaks".

Made famous by Martin Gardner, in his October 1970 column of "Mathematical Games" for "Scientific American" titled:

'The fantastic combinations of John Conway's new solitaire game "life"'.

By that stage Gardner had been writing the column since January 1957, but this particular article received more letters than any article (from any author) previously published by Scientific American.

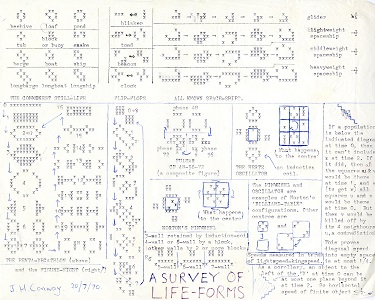

It began with a letter from John Conway to Martin Gardner, containing this page of curious data:

John Conway's Original Survey of "Life-Forms"

Conway had been reading "Automata studies", by Claude Shannon. The initial rules were studied without use of a computer, mostly using a "go" playing board.

After that, life took on a life of its own!

External Links

- LifeWiki: Conway's Game of Life

- Wikipedia: Conway's Game of Life

- Wikipedia: Martin Gardner

- Youtube: Inventing Game of Life (Numberphile) —interview with John Conway